AN EMANCIPATION OF THE MIND, Radical Philosophy, the War over Slavery, and the Refounding of America By Matthew Stewart, W. W. Norton, 374 pages, $32.50

Though the American Revolution inspired the world and continues to influence lovers of liberty, it contained one glaring contradiction. Its proclamation of the equality of all people ignored its acceptance of America’s great national sin of slavery.

With the scholarship and erudition which we know to expect from him, Matthew Stewart traces the development of the American abolitionist movement from the unfulfilled ideals of the Declaration of Independence and the U.S. Constitution to the American Civil War in his latest book – An Emancipation of the Mind: Radical Philosophy, the War over Slavery, and the Refounding of America.

As the subtitle indicates, Stewart sees the abolitionist triumph as a second founding of the republic, and considers its often overlooked leaders as equals in stature – if not status – with the founding fathers.

And, he gives them their due recognition. By interweaving the development of their philosophies into tapestry of intellectual and physical heroism that breathes new life into such familiar names as Frederick Douglas, Theodore Parker, Abraham Lincoln and John Brown while also acknowledging the background influence of others such as Ottilie Assing (a soul mate of Douglas), William Herndon (Lincoln’s law partner and reading advisor) and a host of German refugees from the failed European rebellions of 1848.

Stewart explains how, following our independence, the oligarchic forces of religion, commerce and slavery immediately being chipping away at what they viewed as the country’s dangerous democratic tendencies. But, the flame of 1776 had already lit the fuse for similar revolutions in France and Haiti and had enlightened the minds of German idealist philosophers.

It was the writings of those philosophers, especially Ludwig Feuerbach, that returned to the United States beginning in the 1830s to infuse a moribund abolitionist movement with new energy and tactics to challenge the status quo of what Stewart repeatedly calls “the American slave republic.”

Though Stewart does not make this comparison, we can think of how the Beatles and the British Invasion revitalized American pop music with their reverence for our first rockers and the bluesmen who inspired them. Stewart does not make this comparison, but he indicates that Douglas’s own theories crystallized with his first meeting with Assing. “He only realized where he was going around the time that he opened the door and saw her standing there.” (My italics.)

What Douglas and the others came to realize was that the “moral suasion” of William Lloyd Garrison and the first abolitionists had already failed to change the hard hearts and greedy hands of the slave republic, especially since the churches – both North and South – eagerly cited Biblical authority to justify slavery. The abolitionists quit judging the morality of slavery by the Bible and began judging the Bible’s morality by emancipation.

In fact, preachers such as Parker were reviled as heretics, deists and atheists by the dominant churches, just as the founding fathers had been accused in their own times. (And, yes, these same supporters of the American slave republic “rehabilitated” these new revolutionaries into fundamentalists while also appropriating credit for emancipation that their moral bankruptcy denied them.)

This reinforces Stewart’s own refutation of such lying about the founders in his Nature’s God: The Heretical Origins of the American Republic. There he eviscerates claims by would-be theocrats that the U.S. was founded by fanatical fundamentalist Christians. He directs our glance there with one section title, “Nature’s God Redivivus.”

Similarly, he drops in an homage to Baruch Spinoza with another section titled “The Politico-Theological Crisis.” In Nature’s God, and by extension in An Emancipation of the Mind, Stewart traces America’s political founding to perhaps history’s most hated philosopher since the Athenians condemned Socrates to death for his anti-democratic career at the end of the Peloponnesian War.

Stewart also silently references his previous book –The 9.9 Percent: The New Aristocracy That Is Entrenching Inequality and Warping Our Culture by pointing out how the antebellum South was ruled by the wealthiest 0.1% of its inhabitants and enabled by the rest. That is where America stands today.

There is too much of value in An Emancipation of the Mind to condense. But, we also get stark reminders of the vicious physical brutality of slavery and the southerners’ moral comfort in degrading slaves who were often daughters, sons, siblings and cousins; the connection between the abolitionists and other fights for freedom such as women’s suffrage and fair labor; the benefits of public education – and the southern fear of such; the necessity of expanding slavery since, as a form of cancer, it must grow or die and, just in the reading, how much better educated people were in the 19th century than they are today when spewing hatred passes for political discourse.

I could have done without the section – one of the longest in the book – psychoanalyzing the development of the mind along Hegelian lines. (Its political relevance had already been established.) But, if Stewart wants to prove he can read Hegel with understanding, more power to him.

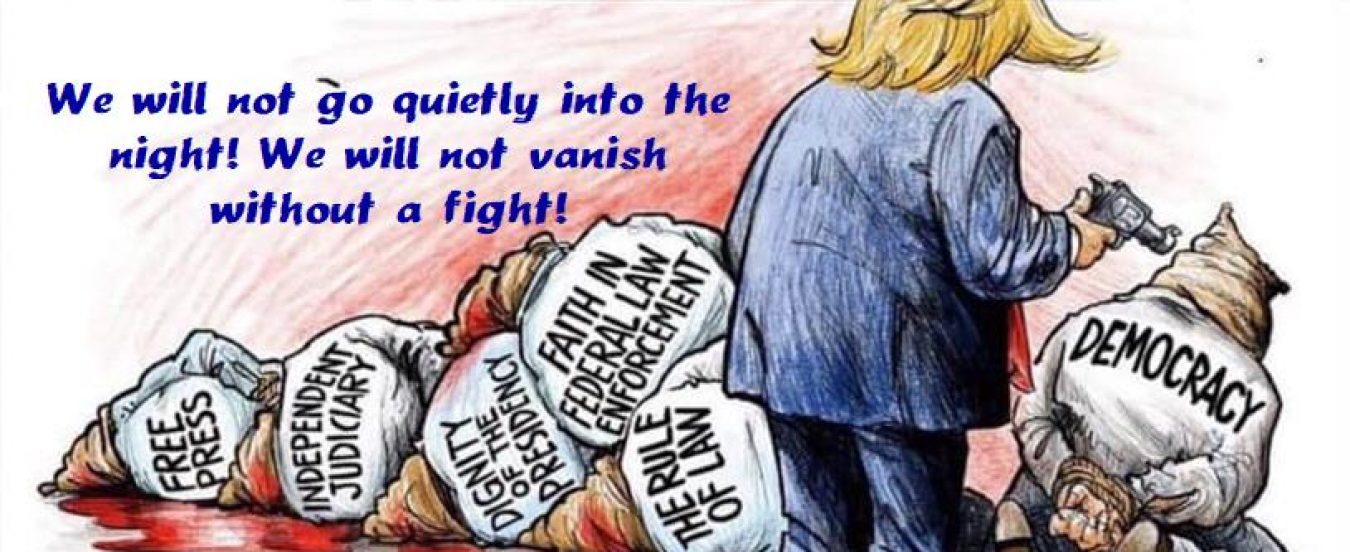

Stewart points out the quick reaction against this Second American Revolution, from the same forces of bigotry and capital and the churches who profit from their complicity is preserving a status quo based on obedience. He says we are fighting the same reactionary movement today. But, I would not be surprised to see him finish off an American political trilogy documenting the rise of the progressive movement from both Roosevelts up through the Great Society until, as Fareed Zakaria points out in Age of Revolution, the progress went too far by trying to extend equal rights to women.

An Emancipation of the Mind is a must read for anyone concerned with the current state of political affairs and how we got here. In fact, anything Stewart writes is worthwhile. He is as erudite as those about whom he writes. And just as refreshingly radical.

(Gary Edmondson is chair of the Stephens County Democratic Party.)